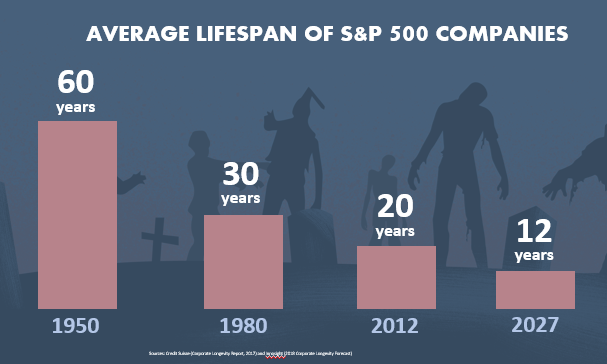

Major corporations need innovation or they die. Some household names like Kodak, Blockbuster and Xerox learned that the hard way. The life expectancy of an S&P 500 company has slumped from 60 years in 1950 to under 20 years today. As the pace of innovation increases, corporations must keep reinventing themselves in order to survive.

It’s not easy for a mammoth corporation to foster new ideas. Often, it makes more sense to snap up a nimble startup than try to reproduce the freewheeling, informal, anti-heirarchical, dressed-down atmosphere that best nurtures tech innovation.

At the same time, emerging startups need the investment, business guidance and management skills that sometimes only major corporates can provide. That’s why so many major corporations get involved with incubators and similar projects where they can connect with startups and sample new technology that could be the key to their own future success.

But what’s the next step? The corporate-startup mating dance can be complex and costly.

The traditional route, assuming a multinational can even find a startup with relevant technology, is a proof of concept, or POC, where the startup conducts a major project within the corporate business to demonstrate the benefits of its technology in a real scenario.

Because they can take considerable time and effort, corporates usually pay for POCs, often providing much-needed revenue for a startup burning through its investments from founding shareholders. But while a successful POC can lead to big orders and might even trigger the acquisition of the startup by its new customer, many POCs end in disaster.

Startups can be lulled into a corporate cul-de-sac, deviating from the creation of a flexible product and their original go-to-market strategy to solving one specific problem for a particular multinational. Unless the POC is constructed in a way that will benefit the entire product, the startup can end up going down a rabbit hole with a particular corporation rather than building a broad business foundation for its technology.

Many potential corporate acquirers will wait until the startups grow larger and have complete products, revenue and customers before buying them. This kind of M&A has become a primary exit mechanism for tech startups – though it can also have pitfalls.

Far too often, the acquirer will be unable to absorb the new company or its entrepreneurial founders into its corporate framework or culture. The product that seemed such a perfect complement to the acquirer’s existing technology stack doesn’t fit as well as expected. A thriving startup can fail as a unit in a larger company and be shuttered without ever providing the expected value.

So the corporations who need this innovation have four options when it comes to investing:

1. Seize an Opportunity

A major corporation has an innovation team – or perhaps a few executives tasked with looking out for new technology that could help the business. Venture investing is not their day job. They come across a cool startup and bring the investment to their board. Its success depends on finding a perfect match with an existing business unit in the larger company.

The decision to invest will be a one off. It is unlikely to scale. It will probably be a specific technology closely tied to the core business of the investor. But most large companies need a broad set of inputs on corporate innovation across many different disciplines. A chemical company needs to keep up to date on much more than chemical innovation and materials.

It must also innovate in process manufacturing, I energy, in cybersecurity, in finance, in marketing, and much more. Most Fortune 5000 companies have broad innovation needs. An opportunistic, narrow one-off deal with a limited focus will not necessarily address the need for new technology.

2. Invest in VC Funds

Another option is for a large company to invest in VC funds that will bring them into contact with startups developing relevant technology. Through co-investing in these companies, the corporation can gain access to useful technology and teams. But finding the perfect co-investment opportunity can be an elusive and expensive pursuit.

A corporation will have to invest between $5 million to $20 million in a regular venture fund to get the necessary access ahead of any rivals. For a corporate behemoth, that amount of money is no big deal, but managing it is a hassle and a diversion from the company’s core business. Such investments rarely end in the kind of match promised by the fund. The return on the investment, even if successful, will barely move the needle for a major global corporation.

3. Corporate Venture Capital

The shortcomings of the first two options have led to the rise of a third option: corporate venture capital or CVC. These are dedicated venture investment teams working within major corporations with a mission to behave like regular VC fund managers, building a portfolio of holdings in startups relevant to the technology and broader needs of the parent corporation. But do the math.

These days, a healthy venture portfolio requires a fund of at least $100-$200 million. Few corporations have the venture capital conviction to give their investment team that kind of money to deploy. A corporation might consider setting up a CVC with $30 million and four or five seasoned executives with salaries and conditions to match their experience.

That means spending as much on management for a $30 million fund as a VC firm running a $200 million fund would earn on its management fees. That’s a huge overhead. It’s unlikely that your in-house team will be able to access the deal flow or have the extensive contacts of a large VC firm. Why pay 10 percent of your fund in fees when you could be paying 2 percent?

Not all corporations are so limited. Some, like Google, Qualcomm and Cisco had huge, billion-dollar CVC funds that proved very successful and became the gold standard for CVC activity. That creates another problem. Just as it can be hard for a major corporation to swallow a startup, it can be just as hard for it to contain a CVC of its own creation.

Fund managers successfully investing hundreds of millions of dollars are rarely content to settle for standard corporate salaries, or answer to boards of directors whose core interests lie elsewhere. These units may have been successful, but they became a distraction to the company’s core business. As a result, many of them have been spun out into separate, stand-alone companies.

4. CVC as a Service

I want to propose a fourth model: CVC as a service. Instead of handing over a multimillion-dollar check to a fund manager, or trying to create an in-house VC, why not work with a platform that offers traditional VC expertise but also allows you to select and curate your own portfolio? This platform makes multiple venture investments with broad enough coverage to provide diversity, but strong enough clusters to demonstrate real expertise in key business sectors.

The corporation gets access to huge deal flow, negotiated terms, and with legal and regulatory work all ready to go. At the same time, investors receive the same privileges as a VC – access to the best class of shares, anti-dilution protection, a place on the cap table, and board representation.

In this model, the corporate investor pays just 2 percent in fees, not 10 or 20 percent, but receives a bespoke service suited to their specific needs and interests.

Sounds familiar? This is the CVC as a service model we are now offering corporate investors at OurCrowd. It’s proving to be popular. We have already signed up several household name multinationals and we expect many more to follow.