The Proposed India Middle East Europe Corridor (IMEC) Offers a Real Opportunity to Usher in Economic Growth Without the Toxic Clauses That Have Undermined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

While the Corridor Is Technically Doable and Makes Economic Sense for All Participants, Fresh Turbulence in the Middle East Is a Source of Worry

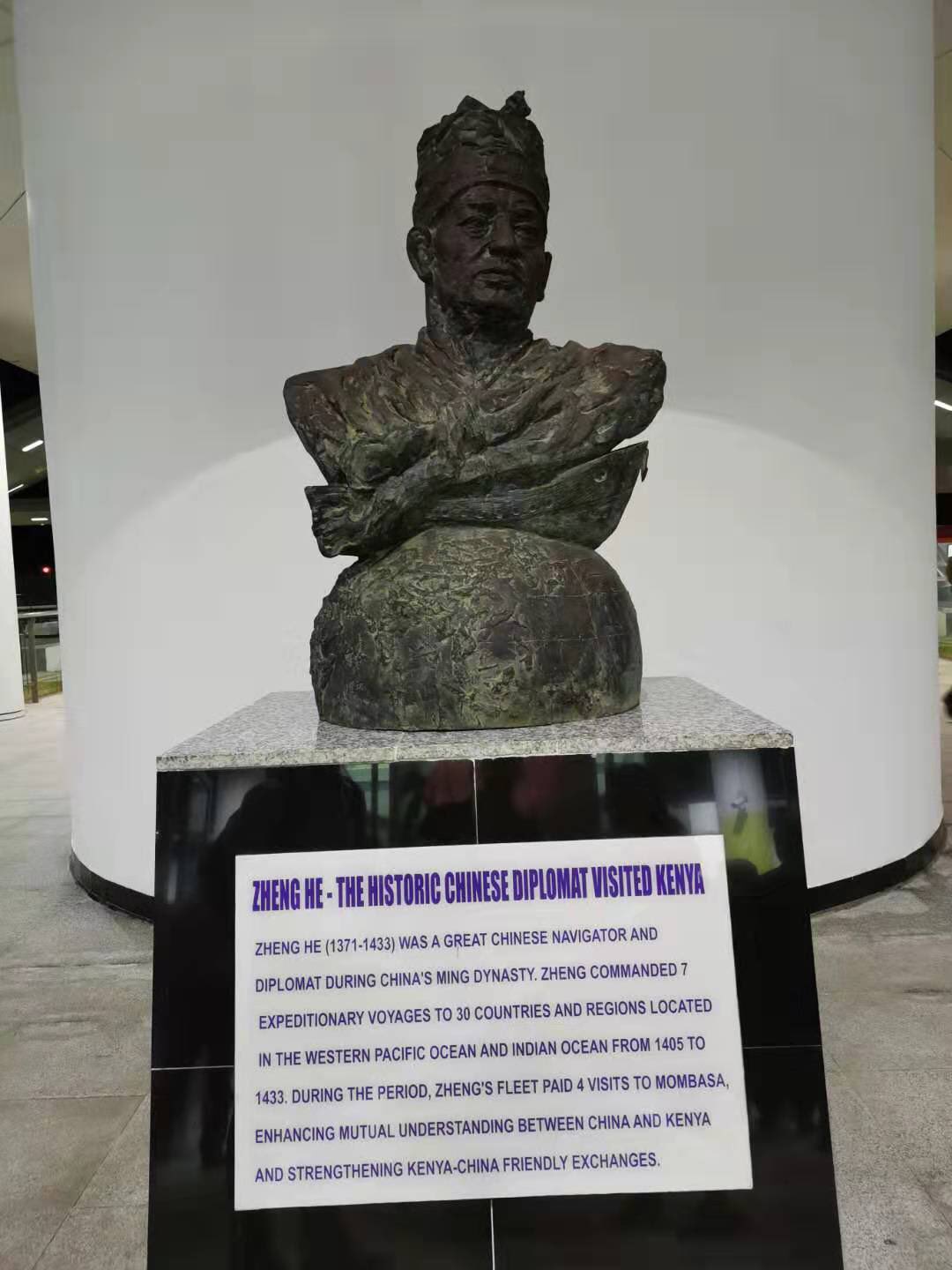

Bengaluru, NFAPost: In Mombasa’s Miritini railway station, passengers alighting the packed trains from Nairobi and elsewhere in Kenya are greeted by the bust of an Asian-looking man set on a pedestal in the main concourse. The description makes it clear that it’s Zheng He, a 15th century Chinese navigator whose fleet had made four visits to Mombasa.

The Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway was constructed by China as a signature project of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Africa. Hence the presence of the bust.

As Beijing gets ready to celebrate the 10th anniversary of BRI with delegates from 130-plus nations — including Russian President Vladimir Putin — arriving at the third Belt and Road Forum on October 17 and 18, Zheng’s bust at Miritini offers the right point of departure to assess its Impact.

Well, for one, BRI has allowed China to be a visible presence in countries where it was once only a distant object of fascination. On the other hand, the political class in Kenya are now coming to terms with the harsh reality that if the railway line defaults on its $3.2 billion loan repayment to the Export-Import Bank of China, the country may risk losing its crown jewel— the Mombasa Port itself — to the Chinese as a recent report in the South China Morning Post said.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry had issued a denial when Kenyan media sounded the alarm about toxic clauses in the contract. But what is undeniable is the fact that the railway, as per the SCMP report, made only $57 million (mn) in revenues last year whereas the annual management fee charged by Chinese operator China Communications Construction Company alone was $120 mn.

A Tale of Two Contrasting Models

Of course, there’s appreciation for BRI in raising awareness about the crucial role played by pivotal infrastructure projects in global development. But of the humongous $966 billion in BRI overseas investments since 2013, $78 billion in loans have gone sour in the last three years. Another $104 billion was lost in sovereign bailouts during 2019 to 2021. This begs the question, “Is there an alternate model?”

This is where the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) comes into the picture. The IMEC is visualised as having two separate corridors. One, the east corridor will connect India to the Arabian Gulf. Two, the northern corridor will link the Arabian Gulf to Europe via Israel.

Though there’s only a memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed by eight participants including India, USA, EU, Saudi Arabia, and UAE last month during the New Delhi G20 summit to go by, and a detailed action plan has to wait till next month, some broad contours of IMEC are visible.

IMEC is positioned as part of G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) for which the grouping’s commitment is to raise $600 billion by 2027 with $200 billion from the USA alone.

Second, PGII prioritises private investment along with the public. A Reuters Breaking Views report recently noted the possibility of government guarantees to parts of investor capital as an incentive.

Of late, projects audited for their social and environmental impact have higher likelihood of access to private capital. So, expect an emphasis on quality projects with high governance standards. In all the above, IMEC already stands apart from BRI, known for its mega projects around the world financed, built, and managed by Chinese companies.

India’s credentials to lead the project are impeccable. India held out when almost the whole world (154 countries as per the BRI portal, says The Diplomat) queued up to sign BRI cooperation agreements with China.

A tough decision given that all our immediate neighbors, except Bhutan, caved in. A critical role for India, along with other countries with heft like Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Israel would ensure that IMEC is more of a collaborative effort than one driven exclusively by the West.

Here too IMEC would stand apart from BRI which is entirely driven by China and implemented by Beijing-owned entities.

The Corridor Needs Political Heavy Lifting

As this article is being published, Tel Aviv has declared war against Hamas after the militant organisation launched a weekend blitzkrieg against Israel which took the country by storm. More than 1,200 Israelis were killed and over 2,800 wounded in the dawn assault staged from both land and sea on Saturday, as per Israeli authorities.

Israel has retaliated, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declaring war and swearing revenge. The Palestinian Health Ministry has claimed 1,200 Palestinian dead and over 5,400 injured as of Wednesday in Israel’s counter attacks.

In addition, Israel said it has recovered the bodies of 1,500 Hamas fighters. But the fact that Hamas has taken Israeli hostages has complicated the situation.

Israel is a crucial component of IMEC. As visualized, merchandise from India and the Arabian Gulf countries would be transported by train to Jordan, from where it would reach Haifa port in Israel before heading to EU by ship.

Crucial three-way negotiations involving Israel, USA, and Saudi Arabia are currently taking place in many locations. Israel hopes it would lead to the establishment of diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia, a powerful country in the Middle East and a leading light of the Islamic world.

When asked whether the war with Hamas could affect the ongoing talks, Gilad Erdan, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, told reporters in New York: “We don’t see any reason that it should be off the table. There are moderate countries in the region that want to normalize relations and live in peace and coexistence and definitely Saudi Arabia is part of them.”

But if anything, the Hamas strike proved how unpredictable events can be in the Middle East. Even a ruler who looks all-powerful like Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman would be mindful of public opinion as he charts his country’s course.

It’s evident that the IMEC corridor needs a lot of political heavy lifting before it can move out of the drawing board. Peace on the ground is a must for the economic corridor to realize its full potential.

An Infrastructure Status Check

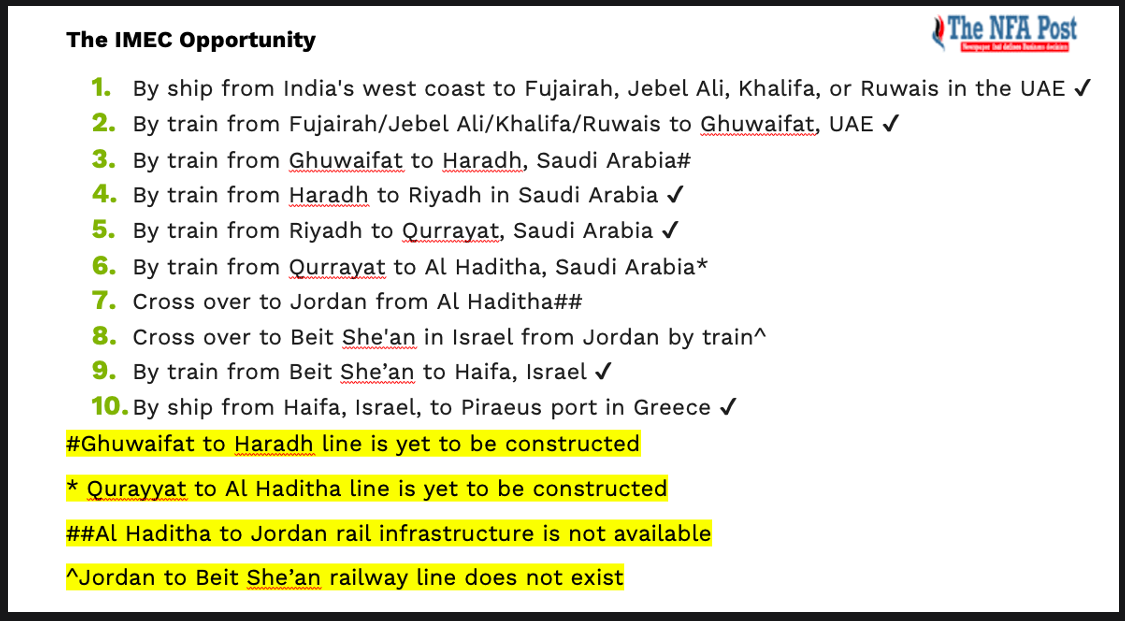

Is the IMEC economic corridor technically doable? A status check on infrastructure on the ground would be insightful here. The good news is there’s considerable infrastructure already in place.

Take the proposed eastern corridor connecting India to the Arabian Gulf. India has more than a dozen functioning ports on its west coast from where container ships and product tankers can set sail to ports in the Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman.

On the other side, there are at least four ports in the UAE (Fujairah, Jebel Ali, Khalifa, and Ruwais) and at least three ports in Saudi Arabia (Dammam, Jubail, and Ras Al Khair) which are at present linked to the railway networks in their own countries. All seven can directly receive and ship merchandise to India. Of the seven, Fujairah is located in the Gulf of Oman and the rest in the Arabian Gulf.

What remains to be done on the eastern corridor is sprucing up the infrastructure and the design of a legal framework for a new trade corridor. This should bring together all necessary paperwork in one workflow. This will ensure the same consignment is not subjected to multiple rounds of clearances.

IMEC’s northern corridor is expected to link the Arabian Gulf to Israel via a rail network, and then ship the goods to Europe from Haifa Port. The foundation to this was laid a dozen-plus years ago when the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) decided to build a rail network connecting member countries.

Though the 2,100-plus km long Gulf Railway is yet to be commissioned, Saudi Arabia and UAE have made considerable progress in setting up rail infrastructure within their own countries.

Not only do the railway lines connect the main freight routes but they also ensure raw materials are transported from mining locations to processing plants near ports. For instance, the Al Jalamid phosphate mine in Saudi Arabia is connected to the Ras Al Khair Port by rail. Again, granulated sulfur can be transported from the Habshan gas field, Abu Dhabi, to Ruwais Port by rail.

What’s missing now is a link from Ghuwaifat in UAE to Haradh in Saudi Arabia (270 km) and the 30-odd km link from Qurayyat to Al Haditha (both in KSA) near the Jordanian border. Once these links are complete, it would be possible for India to ship goods to any of the above mentioned seven ports and move them by rail to the Jordanian border.

A major limitation of the Saudi Arabia Railways is that it doesn’t have freight lines connecting the country’s key Red Sea ports of Jeddah, Yanbu, and Duba. Jeddah, though, has a passenger station on the Makkah–Medina Haramain High Speed Railway, which serves pilgrims. Also, the 124 km-long Jubail to Dammam link, though complete, is not yet operational.

Meanwhile, other GCC members Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar are building rail infrastructure in their own countries. Though not signatories of IMEC, they could come on board and add to the corridor’s momentum once they complete cross-border linkages.

In Israel, a railway network links Beit She’an — often discussed as a possible cross-over point from Jordan — to Haifa Port.

So, a status check on the existing infrastructure gives us a picture of considerable progress already made on the ground. Since the railway lines in all the Middle Eastern countries involved follow the standard gauge, there’s no technical challenge to be overcome on account of break of gauge and bogey exchange.

IMEC Has Obstacles to Overcome

The missing link in Jordan: Though not an IMEC MoU signatory, Jordan is a PGII member. Its location gives it a crucial role in providing the last-mile linkage to Israel. The concern is that railway network is non-existent in Jordan, save for an Ottoman-era narrow gauge line from Amman to Damascus.

Without constructing a standard gauge line (260-odd km) in Jordan and hooking it up with the networks in both Israel and Saudi Arabia, the IMEC corridor will not be functional.

Capital-intensive transloading:

Moving containerized merchandise from ship to rail or vice versa requires container yards for temporary storage, palletising, and processing. Moving liquid cargo from product or oil tankers to rail or vice versa from tank cars to ships require tank farms for temporary storage and processing.

The infrastructure is a pre-requisite to maximise the benefits from IMEC and is capital-intensive.

In contrast, rail transport through land corridors like in the case of the Trans-Eurasia railway from China to Europe doesn’t require capital investment in creation of tank farms or container yards.

Egypt should be in the loop:

Around 26,000 ships pass through the Suez Canal every year which had annual revenues of $9.4 billion as of June 2023. Though it is chock-a-block with traffic, the Suez Canal still remains the most viable route for trade between India and Europe.

The canal is the national treasure of Egypt and Cairo has to be taken into confidence regarding IMEC. Else, there’s a risk that Cairo would view the corridor as an attempt to bypass the canal.

Be mindful of China:

Chinese companies were involved in many a construction project of Saudi Arabia Railways and UAE’s Etihad Rail. As the networks expand, they may bag more projects. Across the Mediterranean Sea, Piraeus Port in Greece, visualised as one of the ports of call for goods headed to EU from IMEC, is owned by Chinese firm COSCO Shipping.

BRI has many marquee projects in East Europe, including the Budapest–Belgrade high-speed railway line. In fact, there’s no getting away from China. Framing the IMEC as a rival to BRI would not be helpful. On the other hand, framing the IMEC as an economic corridor that follows a different model than BRI would be a win-win for all.

Never Discount the Power of Legacy Seekers

Examining the political compulsions of key statesmen who are participants in IMEC is a useful tool to analyze it.

For instance, US President Joe Biden would want to do everything in his capacity to ensure he is not known as the leader under whose watch China sailed past the USA to become the world’s pre-eminent power.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s reference to IMEC in the 105th episode of his monthly radio programme “Mann Ki Baat” revealed his thinking about the economic corridor. He spoke of India suggesting IMEC at the G20 summit.

“This corridor is going to become the basis of world trade for hundreds of years to come, and history will always remember that this corridor was initiated on Indian soil,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

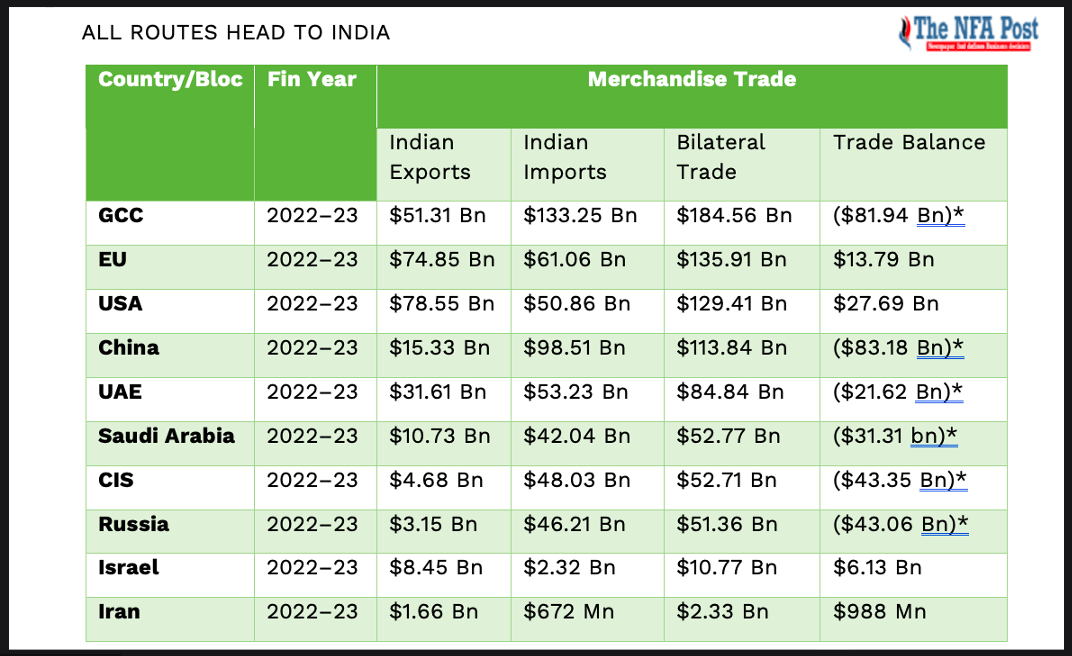

Let’s look at some stats. The USA is India’s largest trading partner with bilateral trade (exports + imports) at $129.41 billion in financial year 2022–23 (FY23). The UAE is India’s third largest trading partner at $84.84 billion. Both are signatories to IMEC.

When it comes to blocs, GCC (which includes Saudi Arabia and UAE) is India’s largest trading partner with bilateral trade at $184.56 billion in FY23. The EU, an IMEC MoU signatory, comes next with $135.91 billion. No wonder the PM has underlined the significance of IMEC.

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman could be guided by thoughts about making an epochal transformation in his country ahead of his formal elevation as the monarch.

Reports on the ongoing talks between Riyadh and Washington stress his determination to secure US help to build a civilian nuclear programme in his country, finalise a Nato-like defense pact, and tie up a deal for advanced weapons supply.

To secure all the above, he may be prepared to water down the terms of the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative and overturn decades of state policy to set up diplomatic relations with Israel.

Benjamin Netanyahu, the longest-serving Israeli premier, knows that overcoming domestic and Saudi resistance to setting up diplomatic relations between the two countries offers him a real shot at cementing his place in history.

Of course, the obstacles are formidable. When contacted by NFA Post, Researcher at German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, Peter Lintl said there is a growing possibility of normalisation between KSA and Israel, but many uncertainties still lie ahead.

“To mention just two: first, what will Saudi Arabia’s stance be on the Palestinian issue? This will determine whether Netanyahu’s current government can agree to the deal. If there are significant political concessions required, it seems unlikely that the far-right coalition partners will agree. On the other hand, it is uncertain whether he can form any other coalition at the moment,” said Researcher at German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, Peter Lintl.

Researcher at German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, Peter Lintl said Second, it is unclear if Joe Biden will secure a majority in Congress; he will not only depend on votes from Republicans but also on the Israel-critical left within his own party.

“Consequently, the deal needs to incorporate elements that can appeal to both of these political camps. If these issues can be resolved, the probability of normalization before the presidential election is high,” said German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Berlin) Researcher Peter Lintl.

When asked whether the ongoing talks among USA, Israel, and Saudi Arabia will result in a breakthrough, Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (AGSIW) Senior Resident Scholar Hussein Ibish told the NFA Post that it seems unlikely.

“Even though Washington and Riyadh would not find it that difficult to reach working understanding on the main bilateral issues, Israel doesn’t appear willing to give any substantial concessions on the Palestinians and the occupation. KSA cannot move forward with normalization unless Israel moves to strengthen the Palestinian Authority and bolster dwindling hopes for a two-state solution,” said Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (AGSIW) Senior Resident Scholar Hussein Ibish.

Both the analysts, however, were confident that the lack of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel would not be an obstacle for IMEC.

“The talks certainly enhance the potential for IMEC. Simultaneously, they signify a broader willingness to strengthen ties with Israel. Therefore, even if the normalisation talks were to falter for any reason, the pursuit of the IMEC corridor may still continue,” said German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Berlin) Researcher Peter Lintl.

Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (AGSIW) Senior Resident Scholar Hussein Ibish concurred that even if these talks don’t produce a rapprochement between the US’ two most significant military partners in the Middle East, the proposed IMEC project could be developed based on indirect or informal understandings.

“It should be focused simply on whatever bilateral cooperation is required for an IMEC corridor. They are parallel processes that don’t absolutely have to intersect, but logically should,” said Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington (AGSIW) Senior Resident Scholar Hussein Ibish.

Israel’s ambassador to India Naor Gilon told the NFA Post that IMEC project represents extraordinary potential.

“It intends to create much more than a railway or an energy route; rather a geopolitical change for the better. A chance for innovation to flourish in the desert and a vital new supply chain from India to West Asia and Europe,” said Israel’s ambassador to India Naor Gilon.

It appears the IMEC corridor perfectly complements the drive of all four leaders — known for their determination to implement policy — to leave behind a worthy legacy. For this reason alone, it would be foolhardy to dismiss it as “as a big pie in the sky” which “sounds like crazy” as a Chinese expert did recently in a talk show aired by broadcaster CGTN.

(With inputs from TheNFAPost correspondents from New Delhi and Dubai)