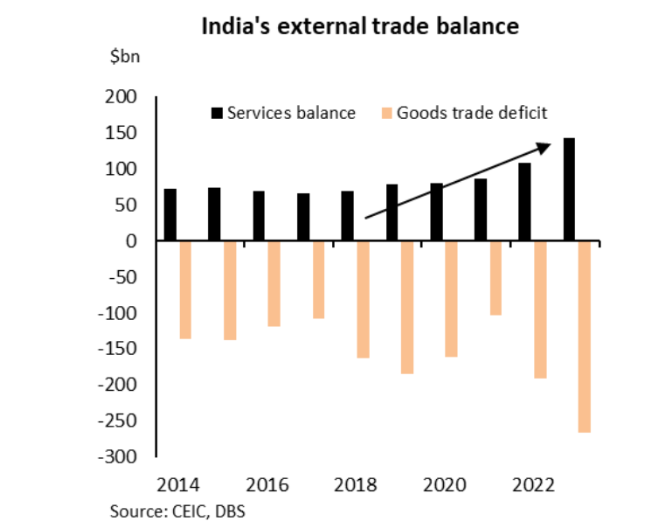

India’s strong service trade performance will add to the improving external balance dynamics this year, in addition to the relief from lower commodity prices (read India: Counting on terms of trade relief and India: RBI’s hawkish pause, firm current account).

Net service trade under the balance of payments (BOP) has jumped from a monthly average of $7.3 billion in late-2019 to $12.9bn in late-2022 and is on course to touch a new of high of $13.5bn in early-2023.

On full-year basis, service exports rose to a fresh high at $320 billion in FY23, marking a second consecutive year of record highs (last year at $255bn). Even as import payments were also up, the full-year trade surplus jumped to $142bn, more than a third higher than FY22.

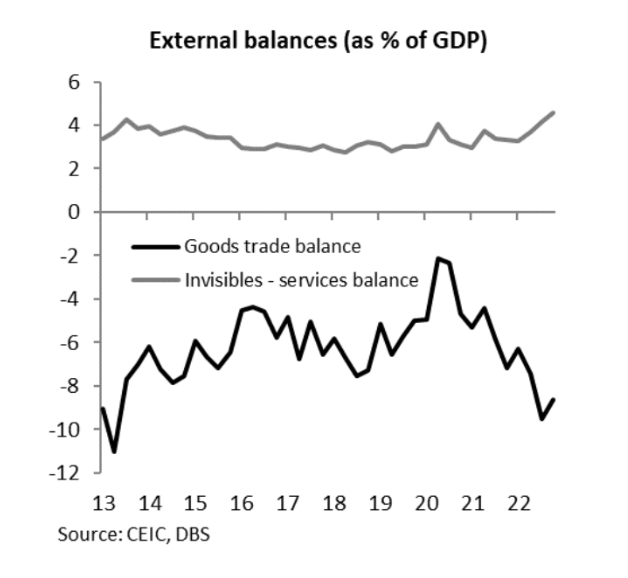

As a % of GDP, share of services under BOP has risen from 3% of GDP in 2019 to 4.6% in 2022 and is likely to have climbed further in the first quarter of 2023. This strength in the service trade balance has been a key offset for the yawning and sticky gulf in goods trade.

What’s behind this strong run

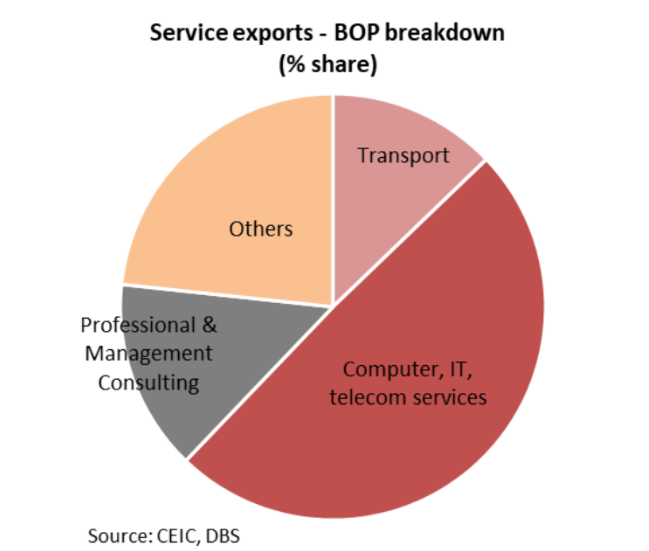

Firstly, Computer, information technology and telecom related sector account for nearly half ($125 billion) of overall service exports under BOP. Of these, computer services make up for the lion’s share.

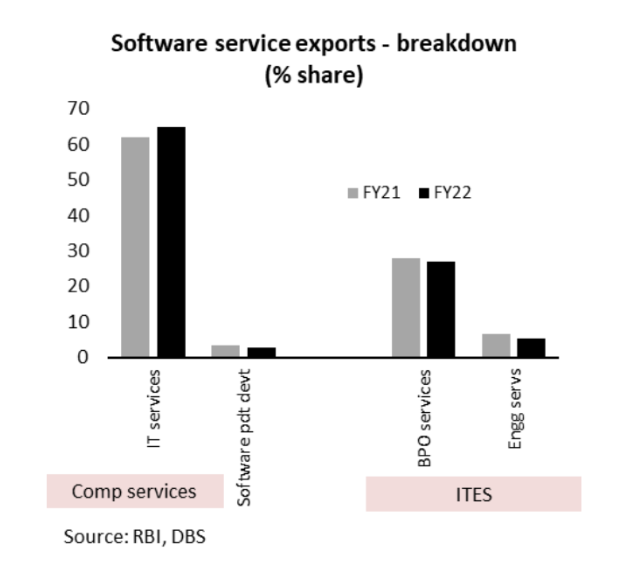

Computer services also account for two-thirds of total software service exports, according to a RBI survey, followed by IT enabled services i.e., ITES. The landscape for software exporters is

dominated by private companies with a 60% share, while that of public enterprises continues to moderate in this space.

About 55.5% of the exports were headed to the US and, followed by Europe, of which, nearly half was attributed to the UK, with the US dollar also emerging as the principal invoicing currency for software services.

Encouragingly, India’s share of computer services in global trade is at a significant 10-11%, better than overall services share of ~4.0% in 2021, as per the ITC. The sector reportedly employs more than 5 million directly and more than double including indirect jobs.

Besides other sub-segments, there has been a noticeable improvement in overall Business Process Outsourcing i.e., BPO services (13% yoy) under ITES, including in verticals like supply chain, business consultancy, finance, and accounting etc.

The IT and BPO services market is projected to grow by a CAGR of 9% by $116bn according to industry group Technavio. From being highly concentrated, this industry is increasingly becoming more fragmented.

Secondly, under ‘Other Services’ the share of professional & management consulting ($37 billion) has been on rising on a strong beat in the past five years. While computer services have risen by a CAGR of 7% since FY16, the consulting vertical has risen by a notable 22% in the same period, contributing significantly to overall service sector outperformance. Gains here are likely driven in part by the growing presence of GCCs in the economy, as we discuss in the next section.

Global Capability Centres expand their heft

What started as Global in-house centres (GICs) has led most companies to widen the scope of these centres to form Global Capability Centres (GCCs), which are dedicated offshore centres of large foreign companies, which handle operations (contact centres, back-office etc.) and technological support.

These centres also capture the evolution from being purely outsourcing operations to climbing up the value chain in terms of business-critical operations and R&D capabilities in state-of-the-art technologies including automation, data analytics, cyber security, cloud engineering, etc.

At a strategic level, these centres might also be entrusted with responsibilities like leading the company’s global vendor management/ sourcing initiatives, whilst marrying operations with technological capabilities, and ensuring back-to-front integration.

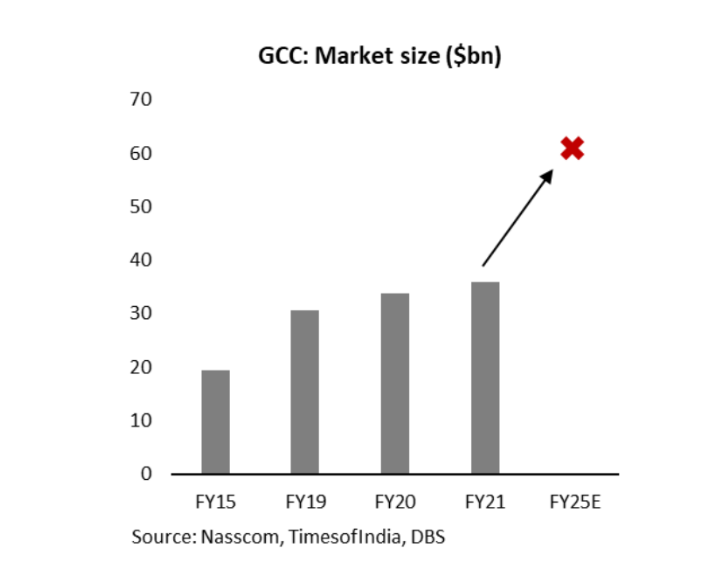

India is currently home to 40-45% of the Global Capability Centres (GCCs) globally. These centres have expanded their footprint at a hastened pace in the past five years, across sectors including BFSI (Banking Financial Services and Insurance), healthcare, and electronics etc.

Increasing digitalisation across sectors and more recently, the need to decentralise as well as diversify supply chains from a single destination, fuelled also by the pandemic, have helped the growth in GCCs. Local availability of a skilled workforce, technological know-how, improving infrastructure and conducive regulatory backdrop have been the key pull factors for international firms opening centres in India.

The growing heft of GCCs in India has carried benefits for the economy by way of rising global expertise (close to 40-45% of all GCCs located in India to the tune of ~1500 centres), employment gains (~1.3mn according to Nasscom), improving technological know-how (over 75% of the GCCs are reportedly investing in higher-order expertise including cloud migration, analytics, Internet of Things), India is currently home to 40-45% of the Global Capability Centres (GCCs) globally.

These centres have expanded their footprint at a hastened pace in the past five years, across sectors including BFSI (Banking Financial Services and Insurance), healthcare, and electronics etc.

Increasing digitalisation across sectors and more recently, the need to decentralise as well as diversify supply chains from a single destination, fuelled also by the pandemic, have helped the growth in GCCs. Local availability of a skilled workforce, technological know-how, improving infrastructure and conducive regulatory backdrop have been the key pull factors for international firms opening centres in India.

The growing heft of GCCs in India has carried benefits for the economy by way of rising global expertise (close to 40-45% of all GCCs located in India to the tune of ~1500 centres), employment gains (~1.3mn according to Nasscom), improving technological know-how (over 75% of the GCCs are reportedly investing in higher-order expertise including cloud migration, analytics, Internet of Things),

The industry body Nasscom projects potential revenues from GCCs to rise from around $36 billion in FY21 (link) i.e., 1% of GDP to more than double to $60 billion over the next five years. Reprieve for the current account dynamics March 2023 merchandise exports fell by a sharp 13.9% yoy, on lower commodity shipments, textiles, engineering goods and gems & jewellery.

Concurrently, imports fell nearly 8% y-o-y, with oil purchases falling on the year but gold imports up sharply by over 200%. The other segments point to slower private sector activity as industrial goods, commodities (price effects) and consumer goods decelerated.

March 2023 trade deficit effectively narrowed but by a large part due to slowdown in imports as much as exports corrected down. The cumulative FY23 full-year goods trade surplus marked a 30% jump from the year before, to stand at $267bn vs $191bn in FY22.

Concurrently, the service trade surplus rose to a record high of $142 billion vs $107.5bn in FY22. Strong service trade surplus is helping to increasingly offset a bigger proportion of the sticky goods deficit (see chart).

We are mindful that the near-term momentum for service trade might turn out to bumpy. Health of software/ computer services rests on the global growth outlook in 2023, especially with the sector heavily exposed to the US & Europe, where policy rates have been aggressively raised since 2022, and is impacting economic activity.

Recent domestic industry trends are also turning cautious, as slowing demand might impact near-term IT spending by various industries as discretionary spends are trimmed. Firms have also been keen on cost

optimisation efforts, marked by labour attrition after last two years of elevated hiring, deferrals

in fresh project execution, and vendor consolidation, impacting not only Tier I but also Tier II players.

Despite factoring in a cyclical modest slowdown in the FY24 service trade numbers, current account deficits are on course to return to comfortable sub-2% of GDP territory in FY23 and FY24, helped also by savings on commodity prices . For the first three quarters of FY23, i.e., Apr-Dec22, the current account deficit amounted to -2.7% of GDP, wider than -1.1% the year before. Going by the narrower trade

deficit (-30% qoq) in the Mar23 quarter and a record-high service trade surplus, there is a likelihood that the current account balance will swing to a surplus.

If this plays out, the four-quarter average current account deficit could be closer to 1.8- 2% of GDP in FY23. With lower imported price pressures (crude oil and other commodities) and strong service sector flows (even after factoring in slower global growth), we expect the FY24 current account surplus to narrow considerably to -1.5% of GDP.

Radhika Rao

Senior Economist, DBS