• The share of developing countries in value-added manufacturing has risen in the past decade

• India’s new manufacturing push, ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ i.e. ‘SelfReliant India’ was announced last year, sharpening focus of the ‘Make in India’ program launched few years prior

• There are global and domestic catalysts for this renewed push

• Expansion of the domestic manufacturing base, through indigenization as well as fiscal incentives, and carving a bigger role in the global supply chain in midst of trade dislocations, are two main priorities for now

• Electronics sector is one of the key thrust areas

• India has room to play a bigger role in the global value chain, with pockets of opportunities

• Lifting domestic manufacturing capabilities will take precedence over multilateral trade agreements like the RCEP

• A larger manufacturing footprint bodes well for growth and external balances

Contours of the manufacturing push and ‘Self-Reliant’ India policy

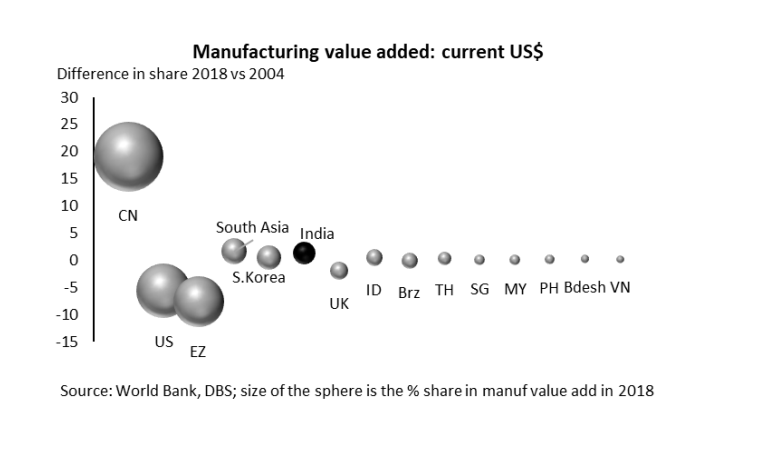

A cross-country analysis of manufacturing value added (current US dollars) reveals that the share of developing countries has risen in the decade and a half to 2018, whilst that of the Western countries i.e. US, UK and Eurozone have slipped.

This is not surprising as cost, efficiency and competitiveness considerations has seen manufacturing activity being outsourced to Asia, particularly China, Vietnam, ASEAN bloc and India.

India’s new manufacturing push, ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ i.e. ‘Self-Reliant India’ was announced in May 2020, to sharpen focus of the ‘Make in India’ programme launched in 2014 and rejuvenate the manufacturing sector.

This shift has been pitched as a move to ensure self-sustenance, echoed in ‘vocal for local’ as well as ‘make for the world’ calls, rather than closing the economy to the world.

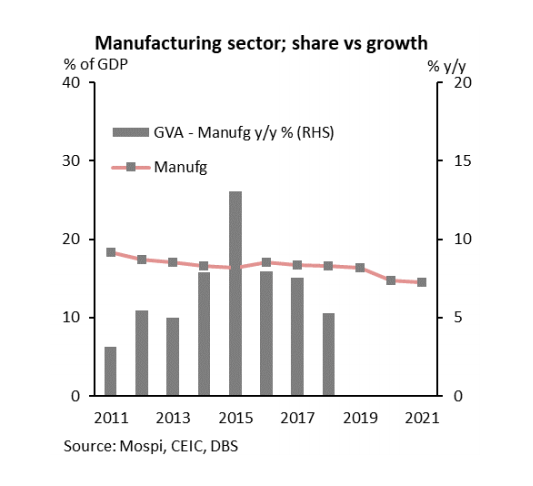

The Make in India (MII) drive launched seven years ago aimed to raise the share of manufacturing to GDP ratio to 25% by 2025, with positive multiplier effects for the broader economy.

Unified indirect tax

Progress has been mixed as the sector’s share has been largely steady since, at about 17-18% with real growth rate slowing to 5% in the past four years vs FY16’s double-digit rise.

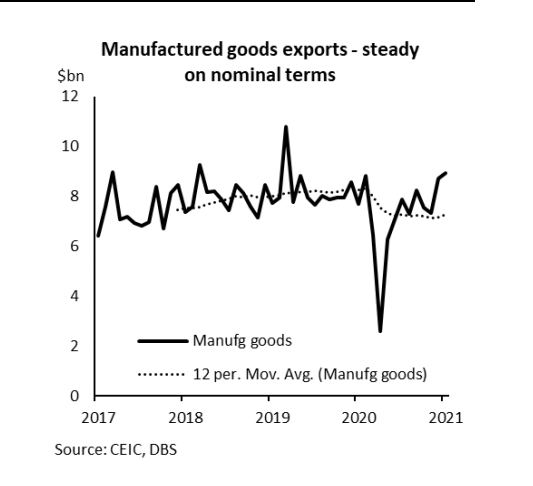

Add to this, manufacturing exports have been flat on nominal basis. On the plus side, there has been a clear emphasis on regulatory reforms, including introduction of the unified indirect tax system i.e. GST, relaxing FDI thresholds, and tariff tweaks.

Part of these benefits were, however, offset by a relatively wider scatter of targeted sectors, absence of directed incentives particularly sales-linked benefits, a shrinking global supply chain/ trade pie and stagnant FDI growth, globally.

Domestic and global catalysts

There are several pull and push factors behind why this reset is being sought.

Globally, trade conflicts and protectionist trade policies have highlighted fragilities of existing global value chains, magnified by the pandemic.

Firms have added resilience and reliability to their matrix of priorities when sourcing supplies and suppliers, in effect widening the net for fresh new potential sources. This has provided a good opportunity for India to enter the fray to attract part of these capacities.

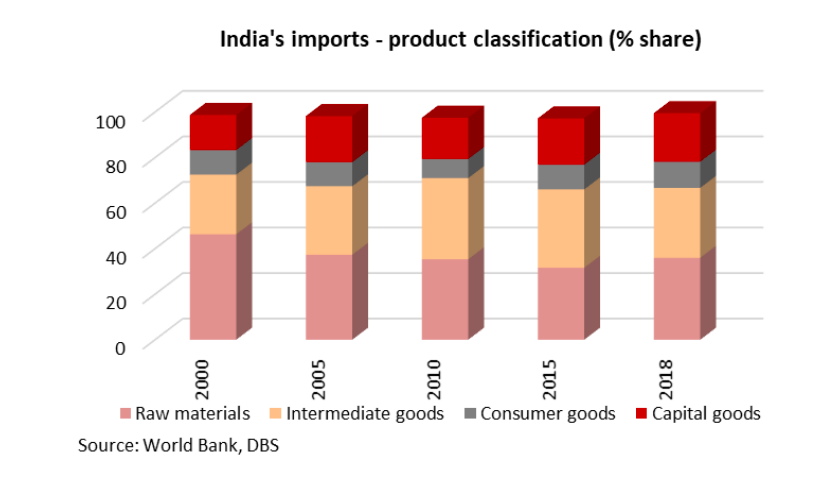

Concurrently, high dependence for intermediate and raw material supplies (see chart below), including manufacturing inputs, underscore the high reliance on imported inputs and consequent vulnerability of domestic supply-chains.

Supply chain disruption

Case in point was the pharma sector where early knock-on disruptions felt in 1Q20 when supplies from China were disrupted due to the coronavirus outbreak led to delays in input availability for key imported drug intermediates.

India’s pharma industry is third largest in the world in volume according to industry data, which might be hurt if supply of crucial ingredients used for formulations are disrupted.

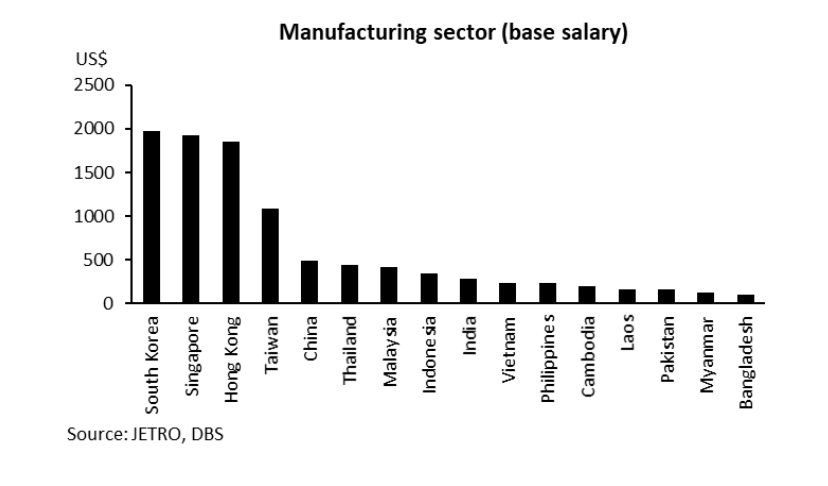

Domestically, there are multiple push factors, including the need to rebalance growth to being more manufacturing-led helped by relatively competitive base salaries vs most production-intensive countries in the region (see chart), according to a JETRO survey.

Another key consideration is need for higher employment generation. India’s labour force is about 500mn, with a little more than half constituting rural workers and rest urban. Over the next decade, India will add c125mn people to the workforce (working age population), likely one of the biggest net increases in emerging markets.

To absorb this workforce, demand and supply responses will be crucial. Supply consisting of labour upskilling and productivity enhancement.

Productivity has moderated in recent years, while the mismatch between skills levels that people have and employer requires remains high. Policy action has been initiated to bridge this deficit, but calls are to raise investment into education, from primary to tertiary levels.

Workforce growth

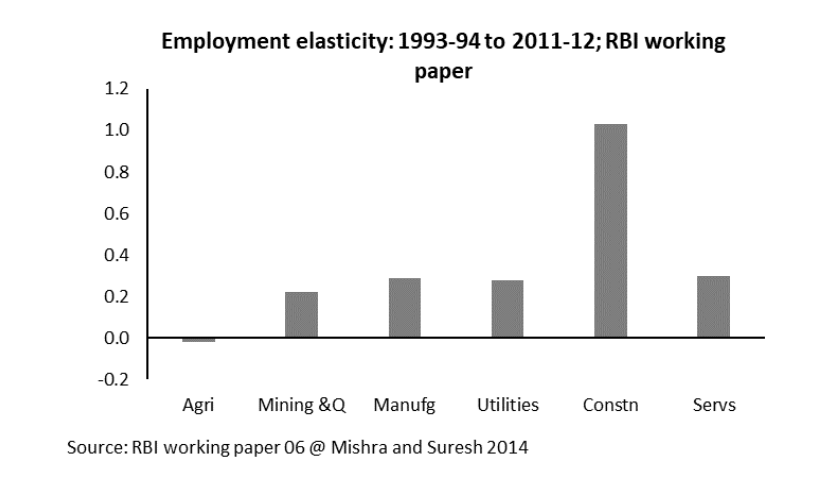

Demand to create viable jobs to keep up with workforce growth. At an aggregate level, agriculture which employs the largest percentage of the rural population has negative elasticity, i.e. employment does not move in sync with growth, which might be leading to regular movement of people out of agriculture to other sectors in search for productive and gainful employment, according to a RBI paper (see chart).

By contrast, utilities, manufacturing, construction, services display high positive elasticity. The recent push to attract manufacturing through local and foreign participation is another effort in this direction.

Framework of ‘Self-Reliant India’ push is a work-in-progress

The framework of the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ drive is a work-in-progress, with two underlying priorities, in our view:

• Expansion of the domestic manufacturing base, to be achieved partly via indigenization and refocus on local value chains, through a combination of import substitution measures (tariffs and non-tariff barriers), sharper industry focus, provision of tax/fiscal incentives, and structural/regulatory reforms

• Carve a bigger role in the global supply chain in midst of trade dislocations. The Global Value Chain participation index highlights India has room to catch-up. Admittedly, the global backdrop is less conducive than 2002-2007, as more protectionist and inward-looking trade policies are being pursued globally. This will also entail efforts to gain a bigger share in an overall shrinking pie.

Domestic manufacturing base

Expanding the manufacturing base through indigenization and encourage diversification to domestic supply chains, as we gather, is focused on:

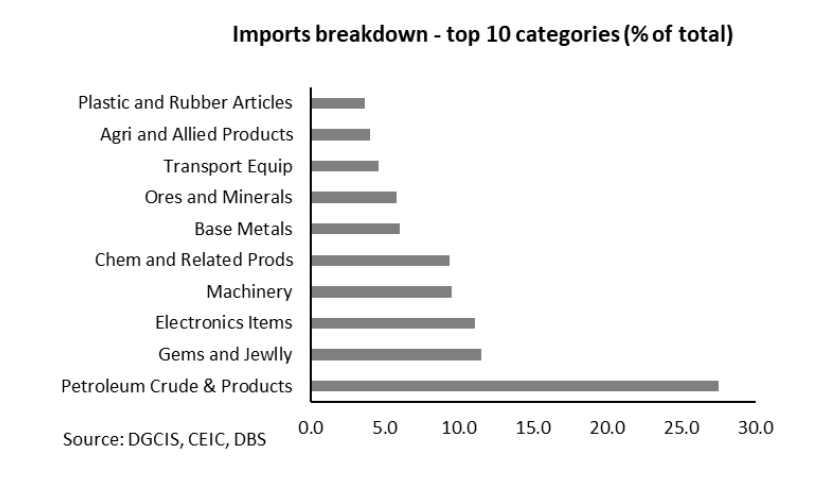

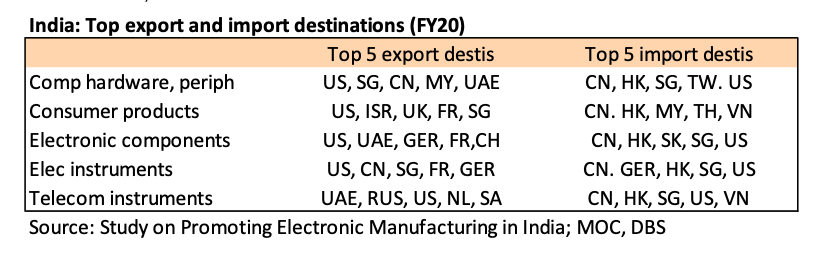

i) Top imported items: while it will be a challenge to substitute imports of crude oil, gold and metals (~half of the basket), authorities are focused electronics, chemicals and pharma, capital goods (machinery), etc. (a third of the basket) – see next chart

ii) Low value-added segments, part of which are labour intensive, including furniture, toys, textiles & clothing, plastics, footwear etc., where imports are higher due to better cost advantage (including cheaper landing costs and quicker turnaround)

iii) Sectors that have high import dependency for inputs such as solar cells/ panels, specialty steel, drugs and intermediaries, auto-components etc.

Part of these indigenisation efforts is being pursued through import substitution, presumably as a temporary aid until domestic capacities are built up.

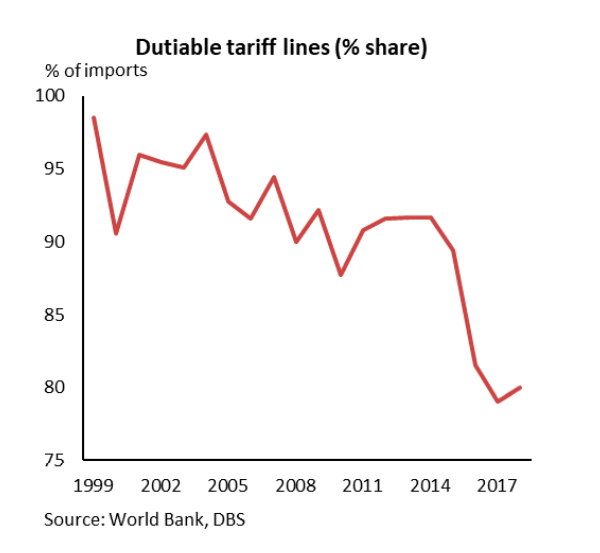

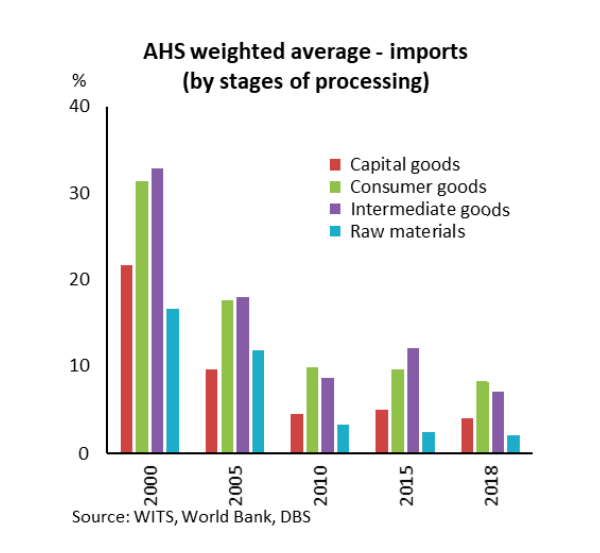

A peek into past trends reveals that the share of imports into India that attract duties has been falling over the past two decades (see chart on left), through a combination of tariffs, non-tariff barriers as well as exportrelated measures.

The effective applied weighted average (%) tariff by stages of processing (see chart on right) have also eased during this period but are still high for intermediate and consumer goods, while also outpacing most regional peers on absolute basis.

Recent budgets have carried an increase in import/ custom duties spanning metals, consumer electronics, inputs for consumer durables, leather, plastic etc., to slow imported alternatives and incentivise domestic manufacturing.

Historical experience with pursuing an import substitution strategy for a prolonged period of time has shown pitfalls, where in higher tariff/ non-tariff barriers might directly slow imports but not necessarily translate into either higher output or materially improve productivity, whilst also rendering exports uncompetitive (in case of re-exports).

Financing, policy efforts

Add to this, pursuing the ‘competitive advantage’ dictum will also ensure that financing and policy efforts are focused on key sectors rather than with a wide scatter.

– Fiscal incentives: Limited gains from the Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) introduced in 2015 in boosting exports, led authorities to consider more targeted measures.

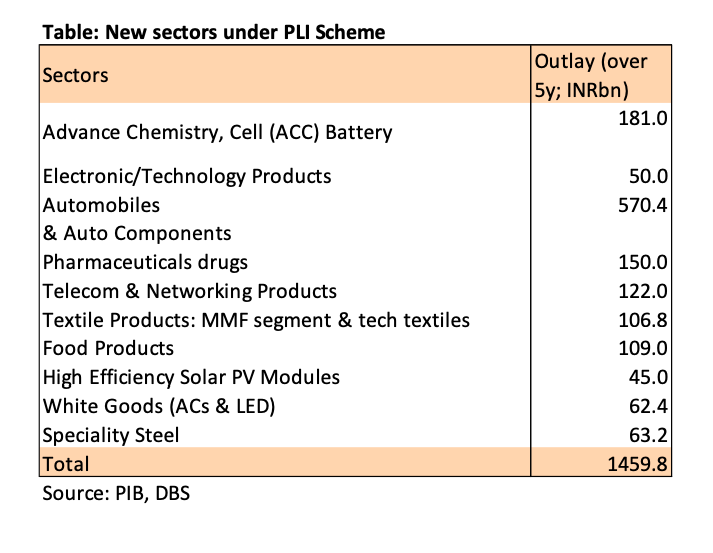

Compared to MII, the Atmanirbhar Bharat push has been accompanied by incentives for selected sectors, tied to production targets, termed as Production Linked Incentives (PLI), announced in March 2020.

Eligibility under this scheme hinges on achieving a minimum threshold of incremental investment and sales of manufactured goods, to the tune of 4-6% on incremental sales (over base year FY20) over the next five years.

The ball was set rolling with the electronics sector targeting the manufacturing of mobile phones and its components as well as bulk drugs. Foreign companies, as well as domestic players, can avail of this facility.

Encouraged by the positive reception, the PLI scheme has been extended to ten more sectors in November 2020 including auto and auto components, textiles, food products, specialty steel, telecom and networking products etc., with the approved expenditure over the coming 5 years likely to equal Rs1.45trn (0.8% of FY21f GDP).

Pulling together this Rs 1.5 trillion (see table above) and Rs 513bn announced earlier, cumulative outlays are around Rs 2.0 trillion (US$27bn). The relatively smaller size of support (per sector), benefits only on incremental sales from last year as a base year and further clarity on the support measures, are aspects which need to be worked on.

Besides electronics (as we discuss below), the pharmaceutical industry is another focus area, being the third largest in the world by volume and 14th largest in terms of value [1].

Impact of pandemic

The sector has a significant ecosystem for development, pharma manufacturing and allied industries, with the ongoing pandemic bringing to light the organic strength of the sector as India Is home to the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer Serum Institute of India, which in partnership with AstraZeneca, is a key manufacturer of the Covid-19 vaccine.

Despite these strengths, reliance on imports is high (particularly bulk drugs, APIs etc.). In addition to boosting bulk drug production, the cabinet recently approved a new PLI scheme with an outlay of Rs 150 billion (US$2.1bn) over a nine-year period till March 2029, covering higher spends on R&D, biopharmaceuticals, complex generic drugs and patented drugs, gene therapy medicines, etc. along with a larger range of bulk drugs and repurposed medicines.

– Structural and regulatory reform push will continue. Apart from the rollout of the goods and services tax system in 2017 to improve predictability of the tax structure and liabilities, corporate tax rate was cut sharply in Sept19, from 30% to 22% (excluding surcharges) for new manufacturing companies and 25% for firms that don’t seek any special tax incentives/ exemptions, in a bid to close in with the Asian peers.

Notably, few ASEAN countries have also followed a similar path to draw in more investors, with Thailand and Indonesia also announcing lower taxes to draw investors.

Reliance on imports

Besides electronics (as we discuss below), the pharmaceutical industry is another focus area, being the third largest in the world by volume and 14th largest in terms of value [1].

The sector has a significant ecosystem for development, pharma manufacturing and allied industries, with the ongoing pandemic bringing to light the organic strength of the sector as India Is home to the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer Serum Institute of India, which in partnership with AstraZeneca, is a key manufacturer of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Despite these strengths, reliance on imports is high (particularly bulk drugs, APIs etc.). In addition to boosting bulk drug production, the cabinet recently approved a new PLI scheme with an outlay of Rs 150 billion (US$2.1bn) over a nine-year period till March 2029, covering higher spends on R&D, biopharmaceuticals, complex generic drugs and patented drugs, gene therapy medicines, etc. along with a larger range of bulk drugs and repurposed medicines.

Manfacturing push – a reset March 5, 2021 Page 9 – Structural and regulatory reform push will continue. Apart from the rollout of the goods and services tax system in 2017 to improve predictability of the tax structure and liabilities, corporate tax rate was cut sharply in September19, from 30% to 22% (excluding surcharges) for new manufacturing companies and 25% for firms that don’t seek any special tax incentives/ exemptions, in a bid to close in with the Asian peers.

Notably, few ASEAN countries have also followed a similar path to draw in more investors, with Thailand and Indonesia also announcing lower taxes to draw investors.

Labour law

Simplifying and modernizing labour laws is another focal point, with plans to assimilate over 40 laws to four codes i.e. wages, industrial relations, social security, and lastly occupational working conditions, alongside nearly 1500 sections into less than 500. For instance, the Code of wages law was enacted in August 2019, with draft rules published in mid-2020 seeking to consolidate four laws covering wages and remuneration.

Keeping up with times, coverage might be extended to gig workers, home based workers, freelancers etc. Broader proposed changes are an important legislative push, considering only a fifth of the total 63mn enterprises have registered under the unified indirect tax system, highlighting the dominance of small and micro enterprises who face an onerous regulatory burden. With labour falling under the concurrent list of the constitution, parliament and states legislatures will be required to work in tandem.

Not only is there a need for intra-state standarisation in procedures but also states will be required to incentive enterprises to scale up, as well as review and reduce multiple processes to improve the ease of doing business for domestic and foreign investors, alike. Easing land acquisition alongside other factors of production will materially improve the ease of doing business and lower related costs.

Electronics sector

There was an early recognition that electronic manufacturing is a critical sector given its contribution to consumers as well as strategic industries.

The period of 1970-2000s witnessed several cycles, kickstarted by publicsector led computer hardware development, which drew in several private sector and foreign players, with a subsequent shift towards IT software development which was promoted by through software technology parks and providing satellite connections to Indian software entities [2].

More recently, besides the presence of large multinational and private sector electronic majors in major segments e.g. telecom equipment, industrial electronics, and hardware, consumer electronics.

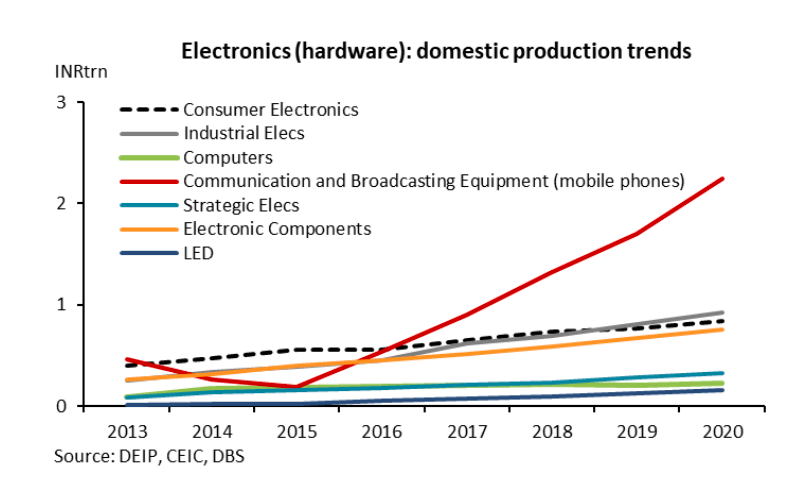

Domestic electronic production has been picking up across segments, with mobile phones and LED output registering CAGR of strong 33% and 26% in the five years to FY20.

Value addition

Until recently, sector’s value addition was limited as most components are imported with the last leg of assembly and sales done domestically, requiring a stronger push to attract manufacturing capacity at the intermediaries and component production stages – for example semiconductors, integrated circuits, printed circuit boards etc.

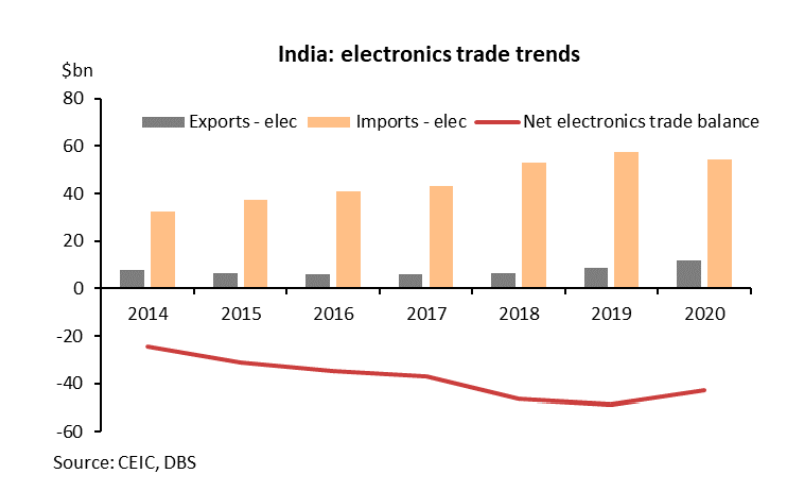

Second to oil, India’s electronics trade deficit is the largest, widening from US$31bn in FY15 to $48bn by FY19, before moderating slightly to $41bn in FY19.

At a granular level, while the shortfall for telecom instruments narrowed in the period owing to rising domestic manufacturing of mobile handsets and components, but that of electronic components doubled as the domestic manufacturers stepped up imports of electronic components and sub-assemblies.

Accordingly, electronic imports have risen from $37 billion in FY15 to $57 billion in FY19. Reliance on crucial components like printed circuit boards and sub-components is high, with key suppliers including China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Exports have fared well in the past two years, rising by an average of 33% in the last two years vs single digit growth in the previous 3-4years, but modest on nominal basis at $10-11 billion.

Steps have been taken to encourage domestic production and attract global names with 100% FDI in the electronics and hardware production and Electronic Systems Design & Manufacturing (ESDM) allowed into the sector.

A National Policy on Electronics was announced in 2019 to expand capacities across the value chain as well as explore new age sectors akin to 5G, AI, Machine Learning etc.

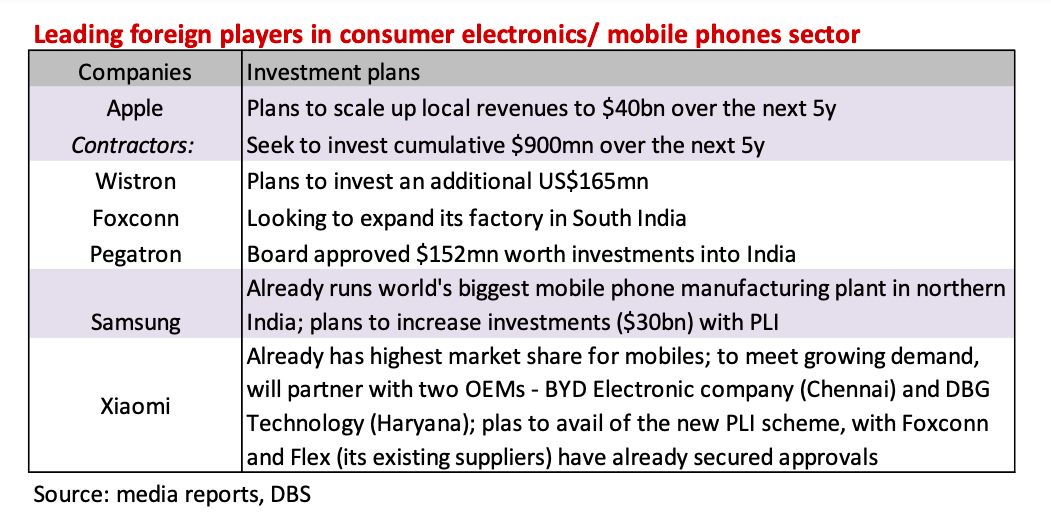

Mobile production

Mobile components and related hardware production were amongst the first few sectors targeted by the PLI scheme. Of the 22 companies who had applied under this scheme, 16 were eligible: a mix of domestic (e.g. Lava, Bhagwati etc.) and foreign (Samsung, Foxconn Hon Hai, Wistron and Pegatron etc.) companies.

Foxconn Hon Hai, Wistron and Pegatron are contract manufacturers for Apple iPhones. Apple and Samsung together account for nearly 60% of global sales revenue of mobile phones and this scheme is expected to increase their manufacturing base manifold in the country, according to the government.

Further, as part of the expanded PLI universe in November 2020, telecom manufacturing and network products is another focus area, which will receive an outlay of Rs 122 billion ($1.7bn) over five years, with expectations of INR2trn investments due to these incentives.

Add to this, the scheme has also been extended to IT hardware manufacturers, targeting production of laptops, tablets, All-in-One PCs and servers.

Outlays are pegged at Rs 74 billion (US$1bn) over the next four years. Industry practitioners had sought this extension, two-thirds of which are currently imported from China, according to the India Cellular & Electronics Association.

Global supply chain

Apart from promoting a higher domestic manufacturing footprint, the other focus area is on increasing integration with global value chains i.e. where production is divided into smaller parts and spread geographically to avail of efficiencies in the value chain.

This has come to fore owing to the US-China trade tiffs and more recently, dislocations brought about by the pandemic.

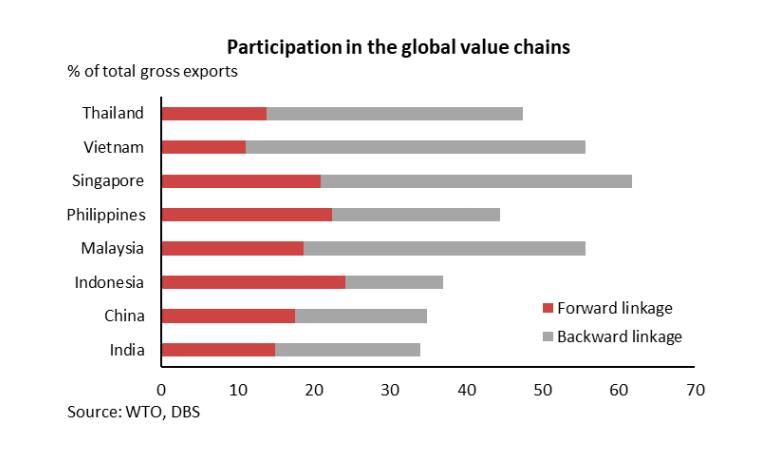

The Global Value Chain (GVC) participation index indicates the connectedness of an economy for its foreign trade, classified as a) backward linkages i.e. share of foreign value-added in total exports, for example, country X uses inputs from Y for domestic production.

In other words, this maps the upstream link, which looks back into the value chain and measures foreign inputs or value-add in the country’s exports; b) forward linkages i.e. domestic value-added embodied in intermediate exports that are further re-exported to third countries i.e. country X supplies inputs for production in Y.

GVC participation

In other words, this maps the downstream links, measuring the domestic inputs/value-add in other countries’ exports. These indices are expressed as a ratio of gross exports, as shown in the chart below.

For India, the GVC participation index has risen in the past decade as trade liberalization caught momentum, courtesy several affirmative regulatory policy changes. Nonetheless, compared to regional peers, India has room to catch-up, in terms of the total participation as well as larger extent of forward linkage.

The recent World Development report highlights four structural factors that help determine GVC participation, including i) factor endowments (low skilled labour and foreign capital); ii) market size; iii) geography; iv) institutional quality; benefits from these strengths can be magnified with appropriate policy changes.

Parts of the renewed manufacturing push, if accompanied by a friendlier tariff/ non-tariff regime, easier access to factors of production and increased productivity will allow India to increase its footprint amongst GVCs.

Economic survey

On the sectoral front, there are pockets of opportunities: a) Sectors where value chains are locally well-embedded and globally recognised (auto subcomponents, chemicals, pharma etc.); b) Areas where there is increasing focus on participating in the global value chains, which includes electronics, machinery and equipment, food-processing etc.

The FY21 Economic survey highlighted ‘network products’ (product lines such as telecom and processing equipment, electrical machinery etc.) as a potential consideration.

Sufficient scale as well as capital and technology linkages with global players is necessary to increase export participation, beyond fulfilling domestic demand; c) Traditional category i.e. labour-intensive sectors where capacities and scale needs to be built, such as textiles, clothing, footwear and toys, pearls & gems etc. where the market share of erstwhile low-cost hubs is receding.

In sectors like footwear, ceramics, apparel, leather, furniture etc., China’s global market share in these product lines has fallen by 2.0-7.5% in the past three years [4].

Multilateral trade agreements

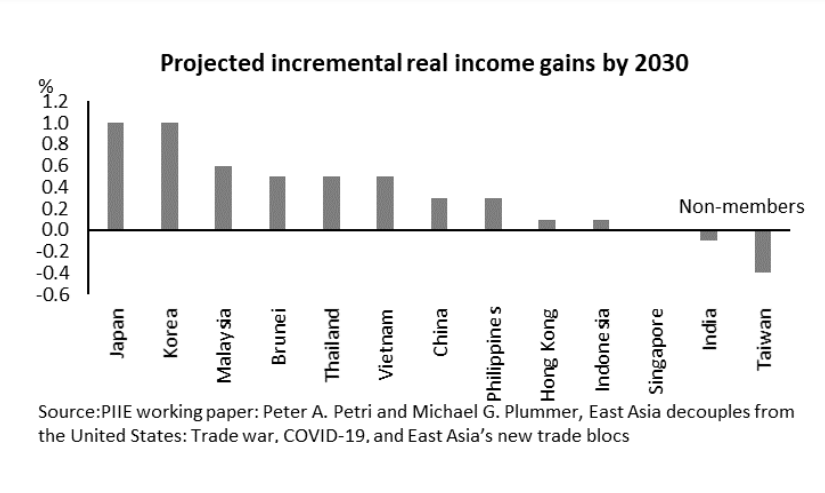

Concurrent to efforts to expand the manufacturing footprint, a debate over India’s move to decide against joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) has ensued.

In the present configuration, the trade impact of RCEP should be mainly on the countries that currently don’t have bilateral FTAs with each other, i.e., China-Japan and Japan-South Korea, in our view.

The door has been left open for India to return to the negotiating table, but the official stance is one of caution considering the already lop-sided trade balance it runs with the RCEP members, especially China (RCEP & India: Weighing the benefits of regionalism).

Limited benefits from previous trade agreements and ongoing push to even out the level-playing field in manufacturing will keep India reticent of joining multilateral trade agreements in the near-term. Incremental real income gains of 1.1% can accrue if India were to join the RCEP bloc, whilst standing to lose marginally -0.1% if it stays out, according to a working paper by the Peterson Institute for International Economics [link].

Economic impact A wider manufacturing base and higher participation in the global value chains, if accompanied by higher job creation (especially if labour-intensive industries receive a fillip), will carry substantial gains for India’s potential growth.

As it stands, fiscal incentives are spread over the next four-five years and are measured for the individual sectors. Nonetheless, this rests on the belief these early benefits will act as a catalyst to draw in the private sector, build higher efficiencies and improve productivity, which in turn will lead to a virtuous growth cycle.

In the past, the rupee has not been tapped to gain a competitive advantage and we expect that stance to be maintained. On the contrary, the INR has faced significant appreciation pressure in midst of strong portfolio and capital flows, which has required the central bank to keep its interventionist bent to guard against strong one-sided moves in the currency.

Effective exchange rate

On real effective exchange rate basis (REER), the rupee was overvalued on 2004-05 base year calculations, but closer to neutral (=100) on the revised 2015-16 indices. On the external sector, the immediate impact is likely to felt on imports, especially sectors where tariffs (and nontariff barriers) have been tweaked in recent announcements.

Material impact on trade imbalances will, however, depend on the extent to which imports are scaled back vs import-intensity of the new local/ foreign companies’ operations. A narrower current account deficit will lower reliance on portfolio inflows, while attracting more non-debt creating FDI flows, improving the overall financing mix.

(Above article is written based on DBS report)